My summary of Andrew Hinton's Understanding Context book in three words would be: “digital disrupts everything.”

Hinton describes at length the different ways in which the digital world disrupts the natural perceptions of logic and understanding that humans have adapted to over thousands of years of evolution. To most effectively design products, services, and information environments in the digital space, we should try to align the design as closely as possible to the innate, perceptive understandings that people have.

Three Modes of Information

Although “information architecture” is in the subtitle, most of this book is not directly focused on IA or the tactical implementations of it. Rather, Hinton works on building a foundation that helps the reader to understand the complexity that the digital world introduces to humans.

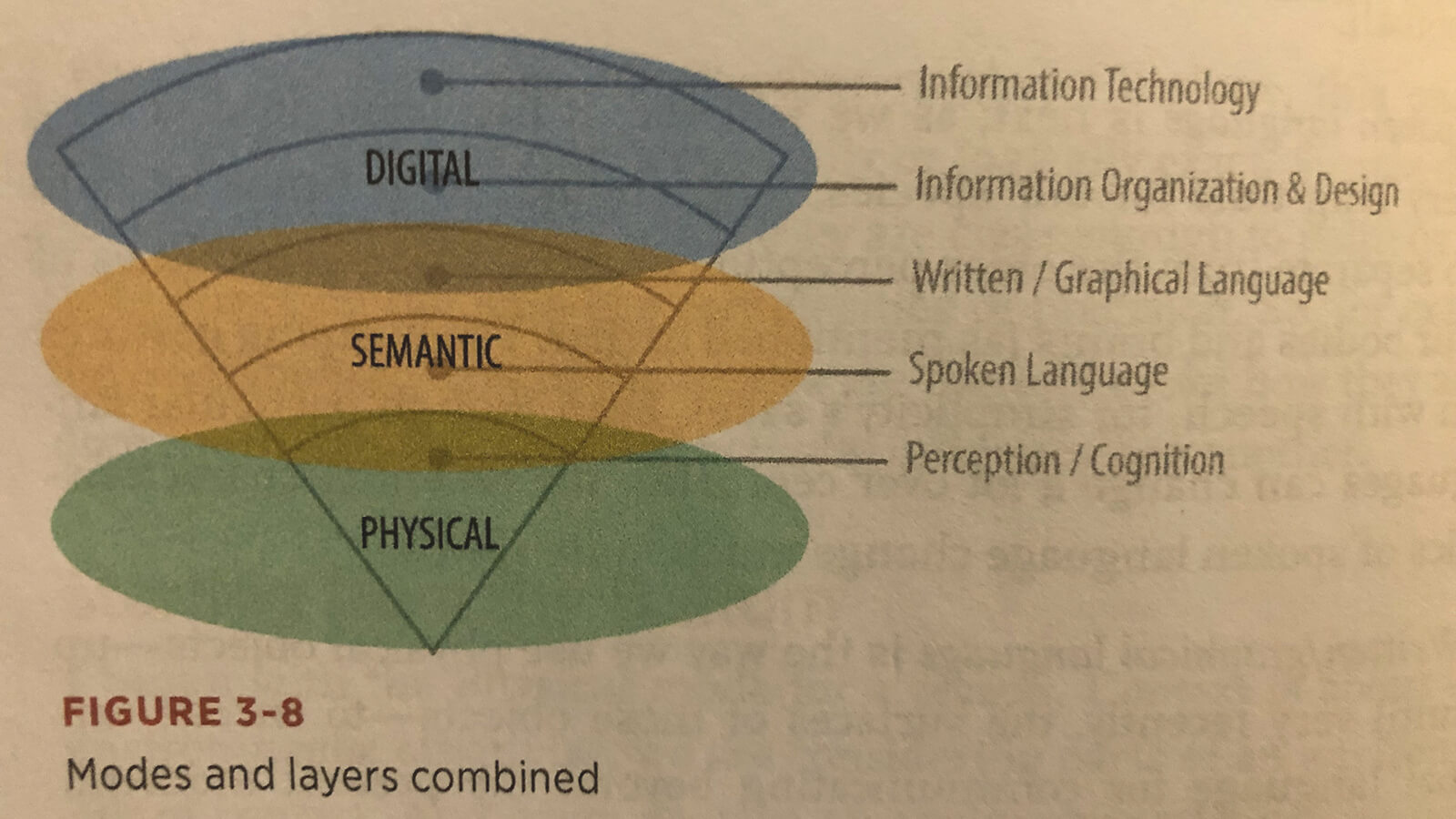

The book is essentially structured around the three modes of information:

- Digital [top level]

- Semantic [middle level]

- Physical [bottom level]

The definitions of these modes, as quoted from the book:

Physical: This is the information animals (and humans) use to perceive their environment for the purposes of taking physical action. It’s information that functions “ecologically” – that is, in the relationship between a creature and its environment.

Semantic: This is information people create for the purpose of communicating meaning to other people (aka, language). This mode includes all sorts of communication such as gestures, signs, graphics, and of course, speech and writing. The semantic mode creates environmental structure for us.

Digital: This is the “information technology” sort of information by which computers operate, and communicate with other computers. Even though humans created it, it’s not natively readable by people.

The below image from the book shows how the different “pace layers” overlay with the three modes of information.

One of Hinton’s central ideas, and that which forms the overarching theme of the book, is that to design the most effective information spaces for humans to understand, we need to start with a bottom-up approach. This paragraph, quoted from the book, pretty much sums things up:

In my experience, most technological design work begins with information technology first and then later figures out the information organization and design and other communicative challenges lower down. Yet, starting with technology takes a lot for granted. It assumes X means X, and Y means Y; or that here is here, and there is there. What happens when we can no longer trust those assumptions? The best way to untangle the many knotted strands that create and shape context is to understand how the world makes sense to us in the first place—with bodies, surfaces, and objects—and build the rest of our understanding from that foundation.

From there, Hinton goes into depth on each information mode. He begins with the physical mode, describing all about the ways perception and cognition form the basis of human understanding, including how much of our thoughts and actions are subconscious and instinctive.

A large portion of this section talks about affordances and the importance of recognizing “intrinsic affordances”, that is, those which we can automatically discern without needing to consciously process and understand (for example, a staircase—its structure leads us to intrinsically know how to interact with it, without the need for any instructions).

The next section discusses the semantic mode, which is essentially all about language, writing, symbols, etc., and how important this mode is because it forms so much of our understanding and context.

Finally, the digital mode section describes all the ways in which the digital world crashes into the naturally built environments of the physical and semantic modes. One of the analogies talks about how with digital, the reaction that happens when we interact with an interface/button may be completely unknown and potentially have disastrous effects, compared to the reaction that happens when we interact with a physical object.

For instance, take the action of swinging a hammer—you know immediately and intrinsically what will happen when you swing the hammer. But with the action of pressing a digital button on a touchscreen—without proper context and understanding, you have no idea what is going to happen when you press the button.

Composing Context

The very last section of the book, “Composing Context,” is where the bulk of the traditional information architecture discussion occurs. Hinton talks about taxonomies, ontologies, metadata, labeling, etc., and how this fits into the picture from the previous sections of the book leading up to this.

One of the important points he hits on is how IA is more than just a website’s navigation or the organization of content—IA needs to first be built on a shared understanding and solid structure from an organizational level. The organization, the team, and the stakeholders need to be aligned in their goals, vision, values, etc. This quote from Hinton states it well:

Trying as hard as possible to resist leaning into literal design is a useful discipline. It avoids using interface solutions as a poor proxy for making real decisions about business models, strategies, and brand definitions.

Wrap Up: Is Understanding Context Worth a Read?

Overall, Understanding Context is a solid UX book that introduces many thought-provoking theories, and prods the reader to think outside the box when it comes to designing information spaces. It’s not an easy read—the book is over 400 pages and discusses many deep-thinking topics that may necessitate rereading some passages to fully grasp everything.

That aside, it hits on many key areas of UX that are helpful in educating us to be resourceful and effective UX professionals. I would recommend Understanding Context for those interested in learning more about the foundation and subsequent methodologies that lead to creating good information architectures.

Share this article with your followers: