What is accessibility? Broadly speaking, it means the ability to access—one's capability to get from A to B in their current environment.

Within the digital world, it can be described multiple ways. Here are some examples:

- Websites, tools, and technologies designed and developed so that people with disabilities can use them.

- The concept of whether a product or service can be used by everyone—however they encounter it.

- Allows users of all abilities to understand, use and enjoy the web, irrespective of their situation, abilities or context.

- The tools you need in the circumstance you find yourself in.

Most often, we think about web accessibility in terms of how it impacts users with disabilities.

Types of Disabilities

While you may immediately think of something like sight impairment, a user may have a disability with any number of functions, including:

- Vision

- Hearing

- Motor/Dexterity

- Cognition

- Mental health

- Speech

Being Disabled Can Take Many Forms

Accessibility isn’t limited to users who have what you might think of as a typical disability. A user may have a permanent, temporary, or situational condition. Consider this example from Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Toolkit:

Statistics on Disabilities and Accessibility

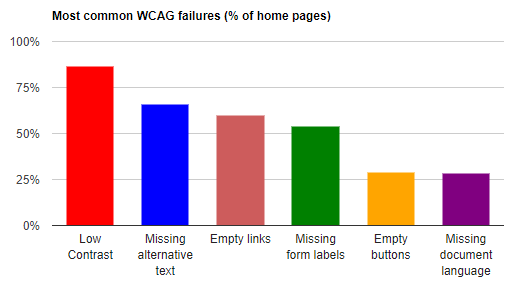

Why is it crucial to get accessibility right? Most notably: because it affects more people than you might think. Check out a few statistics on disabilities and accessibility:

- 15% of the world’s population has some sort of disability. (WHO)

- Up to 70% of disabilities are “hidden”. (Psychreg)

- 90% of websites are inaccessible to people with disabilities who rely on assistive technology. (AbilityNet)

- 82% of customers with specific access needs say they would often return and spend more with a company that provides an accessible online experience. (Click-Away Pound)

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1

Last published in September 2023, the WCAG are a series of guidelines published by the Web Accessibility Initiative of the W3C. They are the international standard for web accessibility.

The WCAG defines three levels of conformance: A, AA, and AAA. Each level requires certain criteria to be met in order to be compliant. The levels have progressively harder criteria.

- A (“Must have”): Failing to meet these standards will prohibit certain groups from accessing web content.

- AA (“Should have”): Failing to meet these standards will make it difficult for certain groups to access web content.

- AAA (“Could have”): Meeting these standards will ensure maximum accessibility and usability for all groups of people.

Most sites aim for level AA compliance. AAA has very strict requirements and therefore is most often targeted by specialist websites serving specific user groups.

WCAG’s Four Accessibility Principles

WCAG defines four principles which form the foundation of its guidelines:

- Perceivable — Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive. This means that users must be able to perceive the information being presented (it can't be invisible to all of their senses).

- Operable — User interface components and navigation must be operable. This means that users must be able to operate the interface (the interface cannot require interaction that a user cannot perform).

- Understandable — Information and the operation of user interface must be understandable. This means that users must be able to understand the information as well as the operation of the user interface (the content or operation cannot be beyond their understanding).

- Robust — Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies. This means that users must be able to access the content as technologies advance (as technologies and user agents evolve, the content should remain accessible).

Common Elements Affecting Accessibility

Page title and headings. Unique, descriptive page titles and subheads are important for screen readers and to orient the user to the content.

Page structure and content hierarchy. Put important headings and words first so that users with a cognitive disability can scan and understand the page as easily as anyone else seeing the page. Be sure to follow a logical content hierarchy that flows together in a coherent way.

ALT text for non-decorative images. Any on-page image with an informational or functional purpose should have ALT text defined, which is essential for screen readers and anyone with visual impairments.

Color/contrast. Do not rely on color alone to convey important information—it may be impossible for users with colorblindness or a vision impairment to discern. Also, be sure to use enough contrast for good visibility (a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text).

Proximity of UI controls. Place controls close together to help users with motor issues be able to operate these interactive elements most effectively. This also benefits people using screen magnification.

Keyboard control. Motor issues may prohibit some people from using a mouse. Ensure that users can navigate the website without a mouse or trackpad, using only their keyboard.

Animation. Be mindful of quick-moving or flashing animation, which could trigger vertigo-like effects or seizures for sensitive users.

Mobile-friendly interface and controls. Ensure that designs are responsive and can be operated easily with standard design pattern gestures, as well as voice recognition, etc.

Target sizes (click/tap). Links, buttons, clickable icons, etc. should be large enough to easily click or tap—this helps not only people with motor/dexterity issues, but also anyone who may have larger fingers or is using alternative methods to click/tap.

Captions/transcripts or ASL for videos/podcasts. This will allow users with hearing impairments to consume the content.

Forms. Forms can be a nightmare even for users without a disability. Therefore, make this experience as seamless as it can be. This includes use of linear tabbing that won’t get stuck, form labels, input fields with proper type (tel, date, etc.), and clear error messages.

Simple Steps to Implement Accessibility Best Practices

- Use extensions like WebAIM’s WAVE extension, color contrast checkers, page hierarchy crawls, and other similar tools to evaluate your pages.

- Conduct site/page audits for accessibility issues.

- Keep accessibility in mind when proposing new content/site tools, designing user flows, reviewing/optimizing pages, and doing QA.

- Prioritize fixing issues whenever possible.

- Develop personas of users with various degrees of disability.

- Keep learning! Read blog articles/reports, watch training videos, and familiarize yourself with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. Engrain accessibility as a default priority in all of the UX/UI and web content work that you do.

Share this article with your followers: